The Truth Is Out There, but Can We Believe It? Elisabeth Bik and the Quest for Science Integrity

Flavia-Bianca Cristian

What does scientific fraud have to do with science communication? Their relationship may be complicated, but addressing the persistent issue of public mistrust in science is central to their connection. To shed light on the dynamics of trust in science, we enlisted the help of Dr. Elisabeth Bik, a scientific integrity consultant by vocation, who graciously offered us an interview to quench our curiosity.

Image by Kerry McInerney

I always thought my own curiosity for biology started with watching Dr. Quinn, Medicine Woman with my mom as a child. It turns out that was just the symptom; the real cause was watching The X-Files. Have you heard of The Scully Effect? A study showed that 63% of women familiar with Agent Scully from The X-Files had greater confidence in pursuing a STEM career. The irony is that I thought this TV show perfectly illustrated how different my mom and I were—her interest in the paranormal clashing with my life philosophy, being the scientific method. Yet, decades later, I realize we were both gripped by the same human impulse: the relentless quest for answers. For my mom, those answers were allowed to be in the unknown; for me, they must stand up to scrutiny. My recent interview with Dr. Elisabeth Bik gave me a new context for understanding skepticism as a tool, one that is indispensable for producing an invaluable product: trust.

Dr. Bik, a scientist, has transformed into the scientific integrity consultant known globally for her meticulous work investigating image duplication and scientific misconduct. She has shifted her career focus, but her core mission remains the same: she is in the business of producing and protecting trust in science. Curious about this new path she forged—part sleuth work, part science communication—we set out to dissect Dr. Bik's job description to understand the impact of research integrity work not only on the scientific industry as a whole, but also on how science is perceived.

The Science Communicator Badge: Who Qualifies?

Before becoming well-known for her work concerning scientific misconduct, Dr. Bik was a microbiologist whose research spanned from cholera vaccines to the microbiome of dolphins. Perhaps not surprisingly, even back then, she was concerned with context and made a conscious effort to talk about her work beyond the circle of experts surrounding her. She recalls how, in her PhD thesis, which focused on cholera vaccine development, it was important for her to tell the story of how Robert Koch had discovered the cause of cholera. Later, when she was working in the US, she launched her first science communication Twitter account discussing microbiome research.

Source: Dr. Bik, Photo by Clara Mokri

When I asked her if she considers herself a science communicator, she hesitated for a second before explaining, “I guess I do see myself as a science communicator, yes. I am active on social media, and I give lots of talks about my work. It is not necessarily for a lay audience; most of my talks are for a scientific audience, but with Twitter, Bluesky, and LinkedIn, I hope to reach a much wider audience”. Though essential, her concern for context and enthusiasm for science are only half of the story.

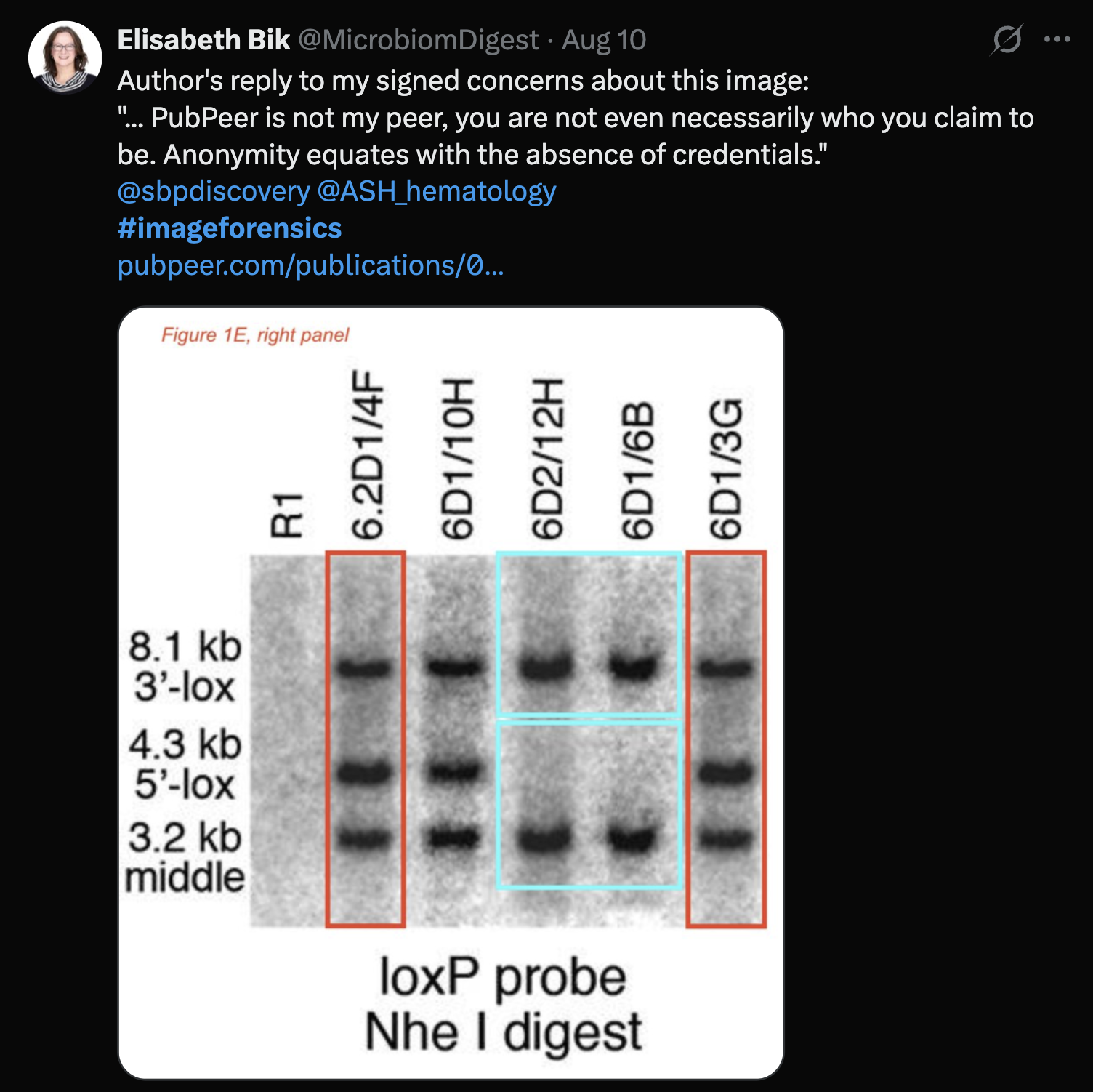

What I admire most about Dr. Bik’s approach to science is her sheer courage, her willingness to have difficult conversations. As if investigating scientific misconduct were not proof enough of this, Dr. Bik gave me another example of her bold approach when she told me she still has a Twitter account (yes, she insists on calling the platform by its old name) in addition to her relatively recent Bluesky account. She argues that we still need scientists in spaces that are being overwhelmed by mis- and disinformation. My suspicion that this brave mission does not come without a cost was confirmed when we talked more about the surprising elements of this job. “I had not expected (all the) insults that are slung at me over social media,” says Bik, confirming that she does agree that this kind of aggression is fostered by the very nature of social media, which allows a global community of anonymous users to partake in various forms of peer pressure and bullying. Unfortunately, this pushback isn't confined to the screen. Elisabeth Bik has received legal threats because of her work, and I am particularly struck by the impressive legal knowledge she has been compelled to acquire, a skill set not many working microbiologists ever anticipate needing.

When I dare to mention that some scientists and science communicators are wary of those who highlight scientific misconduct and blame them for a lack of trust in science, she dryly starts by telling me she is well aware of it. She goes on to explain, with the tenderness of someone who cares for a beloved flower garden, that she likes to use the rotten apple metaphor when explaining to her audiences why she is not necessarily the carrier of bad news. “We need to take out the rotten apple before it infects all the other apples or fruits in the basket. I am not saying that the whole fruit basket is bad; there are beautiful apples and oranges in there. We need to take one bad apple out, and that is what I am trying to do, because then the whole science will be better.”

From Scientist to Detective: How does it work?

How does one become a professional scientific integrity consultant? I asked Dr. Bik if her training as a microbiologist was enough for her new role, or if she had to retrain herself in sleuthing. “There is no training for it, I couldn’t take a class,” Bik says cheerfully, explaining that she had to learn to think more like a molecular biologist than a microbiologist, given that her specialty quickly became image analysis, and particularly spotting image duplications. She did design what could be considered a crash course for herself by investigating over 20,000 papers in collaboration with two other scientists who were well-versed in publishing and science integrity issues. The trick was the need to reach consensus on the articles they investigated—which meant they had to ‘grow towards each other,' as Bik beautifully puts it—and thus further developed their expertise in assessing the likelihood of fraud or misconduct in molecular biology publications. My conclusion is that a natural talent for pattern detection, in addition to her solid scientific background and her continued interest in science communication, made Dr. Elisabeth Bik the ideal candidate for the job.

The Future: An Army of Science Detectives?

Source: Twitter

In my enthusiasm for what sounded like a new kind of science job, I asked Dr. Bik if she thinks the future entailed a small army of science detectives with her skill set and dedication. She gently tempered my childish enthusiasm by explaining that this kind of “policing,” or rather, quality control, should remain primarily the job of publishers. Her stance about the involvement of the law in this matter was ambivalent. “You would hope that science would correct itself, but it doesn’t,” says Dr. Bik, but she admits that legal proceedings usually slow down this process by making it harder to retract a paper, for example. However, the inherent barriers in the system do not stop her from doing something about this issue now. Part of her mission is to train and empower other scientists to spot misconduct themselves. By cleverly using social media and creating the hashtag #ImageForensics, she has seamlessly trained scientists all around the world in her craft. These days, Dr. Elisabeth Bik is occasionally asked to be a consultant in a legal case or for a publisher, but she dedicates most of her time traveling around the world and educating academics worldwide on scientific misconduct and all of its nuances and pitfalls.

Beyond the X-Files…

I think we can all admit that between the experience of the pandemic and the advent of widely-accessible AI, the scientific landscape inspires more fear than fearlessness. The X-Files ambiance is not confined to 90s nostalgia but has made a comeback of sorts. Apart from being truly inspiring, my interaction with Dr. Elisabeth Bik has offered me a new framing of the scientific world. Science is an industry, not a religion. In a scientific economy where trust is the ultimate currency, the need for genuine, sustainable trust in science has never been clearer. Against this backdrop, where public trust in vaccines and even guidance from institutions like the CDC is wavering, the path forward is singular: scientific integrity and science communication must work hand in hand, not in silos, to secure the foundation of science for the future.