How Fancy Comma continues to be the torchbearer for voicing Science Policy Change

Eisha Mhatre

In the whirlwind of early 2020, just before the world shifted dramatically, Sheeva Azma launched Fancy Comma, LLC, a science communication consultancy with humble aspirations. Little did she know that a global pandemic would catapult her startup into the heart of both science communication and the pressing realm of science policy.

"As the pandemic spread, so did misinformation," Sheeva reflects. "And while Fancy Comma grew to meet the moment, it became increasingly clear that the institutions supporting science in the U.S. were far more fragile than I had realized. Today, that fragility is structural, and it is political."

Changing tides for research funding in US

The National Science Foundation's drastic decision in April 2025 to halve its Graduate Research Fellowships sent shockwaves through the scientific community. This wasn't just a budget cut; it was a signal that science might not be the national priority it once was. Grants are increasingly scrutinized for political reasons, and even researchers at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), traditionally secure, are facing threats. These pressures disproportionately affect public universities and state labs, which lack the endowments of elite institutions. Major science hubs on the coasts often dominate narratives; still, science also thrives in places like landlocked Oklahoma, a flyover state to those who do not live there, with its focus on public health, weather, agriculture, and energy. The infrastructure and researchers are there, but visibility and support are lacking.

Sheeva Azma at the Oklahoma State Capitol on March 7th this year. Photo Credit: Rachel Nichols for the OU Daily

In March, Sheeva organized a "Stand Up for Science" rally in Oklahoma City. Over 100 scientists, engineers, and advocates gathered at the State Capitol to raise awareness about the threats to scientific funding and academic freedom. Lawmakers joined in, echoing concerns and welcoming engagement. Stand Up for Science took place simultaneously at 30 sites across the US, from New York to Montana.

“At our rally, several lawmakers from the Oklahoma House spoke. One was a computer scientist, and two were former educators. We also had the lawmaker who represents the University of Oklahoma. Altogether, it was a group of people with a strong investment in science as an enterprise,” says Sheeva. Oklahoma also harbours the National Weather Center in Norman, which is a federally funded weather research center that is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and has also been hit by political layoffs. The rally saw the representations from both the biomedical and atmospheric sides of science, as well as other science fields, though Norman’s National Weather Center had its own protest as well.

"The event was energizing but also revealing," Sheeva notes. "Despite its significance, media coverage was sparse, reflecting a larger problem: science in 'middle America' is often overlooked."

Stand Up for Science rally in Oklahoma. Photo Credit: Rachel Nichols for the OU Daily

Yet it is precisely in these communities that engagement matters most. For example, Oklahoma's Representative Tom Cole, chair of the House Appropriations Committee, determines how much federal money goes to NIH and other agencies. He is a Republican who has consistently supported biomedical research. That kind of bipartisan support for science exists. But it requires effort to maintain, and scientists must be part of that effort.

Many scientists hesitate to speak out, fearing professional repercussions. However, organizations like Science Impacts have stepped in to help researchers understand how funding decisions ripple through labs, hospitals, and classrooms. Resources from outlets like eLife are encouraging more robust civic engagement by scientists, including guidance on interacting with legislators and advocating evidence-based policy. Still, institutional culture often discourages advocacy. Scientists are trained to value objectivity, avoid politics, and to publish rather than protest. In a moment where science itself is politicized, a new kind of professionalism is needed, one that sees communication and policy engagement as integral to a scientist's role.

From D.C. to Oklahoma: How Sheeva Found Her Voice in Science Policy

Sheeva's journey into science policy began during her graduate studies at Georgetown, where, as a Society for Neuroscience Young Advocate, she learned how Congress operates and why effective communication with lawmakers is essential. She also took science policy courses, including ‘Public Policy for Scientists’, taught by local policy professionals. One of her lecturers, Kei Koizumi, later became the science advisor to Presidents Obama and Biden. During that time, as the Affordable Care Act was being debated, Sheeva immersed herself in comparative health policy and learned firsthand how science and legislation intertwine.

She then interned at the Potomac Institute for Policy Studies, a think tank formed after Congress disbanded the Office of Technology Assessment in the 1990s. The institute advises government leaders on research, development, and technology policy, covering everything from semiconductors to biomedical innovation, with a distinct dual focus on defense and science.

"The federal government funds all of federal science in academic places," Sheeva realized, "That means the federal government can influence the way science goes and what is studied." The current political climate is unprecedented, with grants being defunded for political reasons, and more people need to be aware of this. Moving from the hub of Washington, D.C, to Oklahoma provided a different view. In smaller states, it can be harder to get national attention for science issues; thus, local engagement becomes even more crucial.

“The national media often portrays health issues as problems of red states,” comments Sheeva. “While the recent measles outbreak in Texas spread into Oklahoma, it was barely covered in the news. During the COVID-19 pandemic, too, Oklahoma City was briefly mentioned as a hotspot at 3 a.m. on the overnight national news, and then never again, even though the state ranked among the top ten in deaths.”

She sees a similar pattern in other crises. The devastating wildfires in northeast Oklahoma in March made brief national headlines but quickly disappeared from the conversation. Sheeva insists that Oklahoma has a vibrant, underappreciated scientific community. While Washington, D.C., remains a powerhouse of research with the NIH right there in Bethesda, she emphasizes that strong science doesn’t only happen near federal institutions. Many of Oklahoma’s scientists and educators are deeply committed to advancing research and public health, even without the spotlight.

“One thing that we want to do at Fancy Comma is encourage people, regardless of where they live in the U.S. or even worldwide, to get involved, depending on how receptive their governments are. Some governments are more accepting of people's input than others. There are a number of different governments and organizations that support science around the world. Here in the U.S., anyone can meet with their lawmakers. Federal lawmakers have offices in Washington, D.C., as well as state offices that you can visit,” says Sheeva.

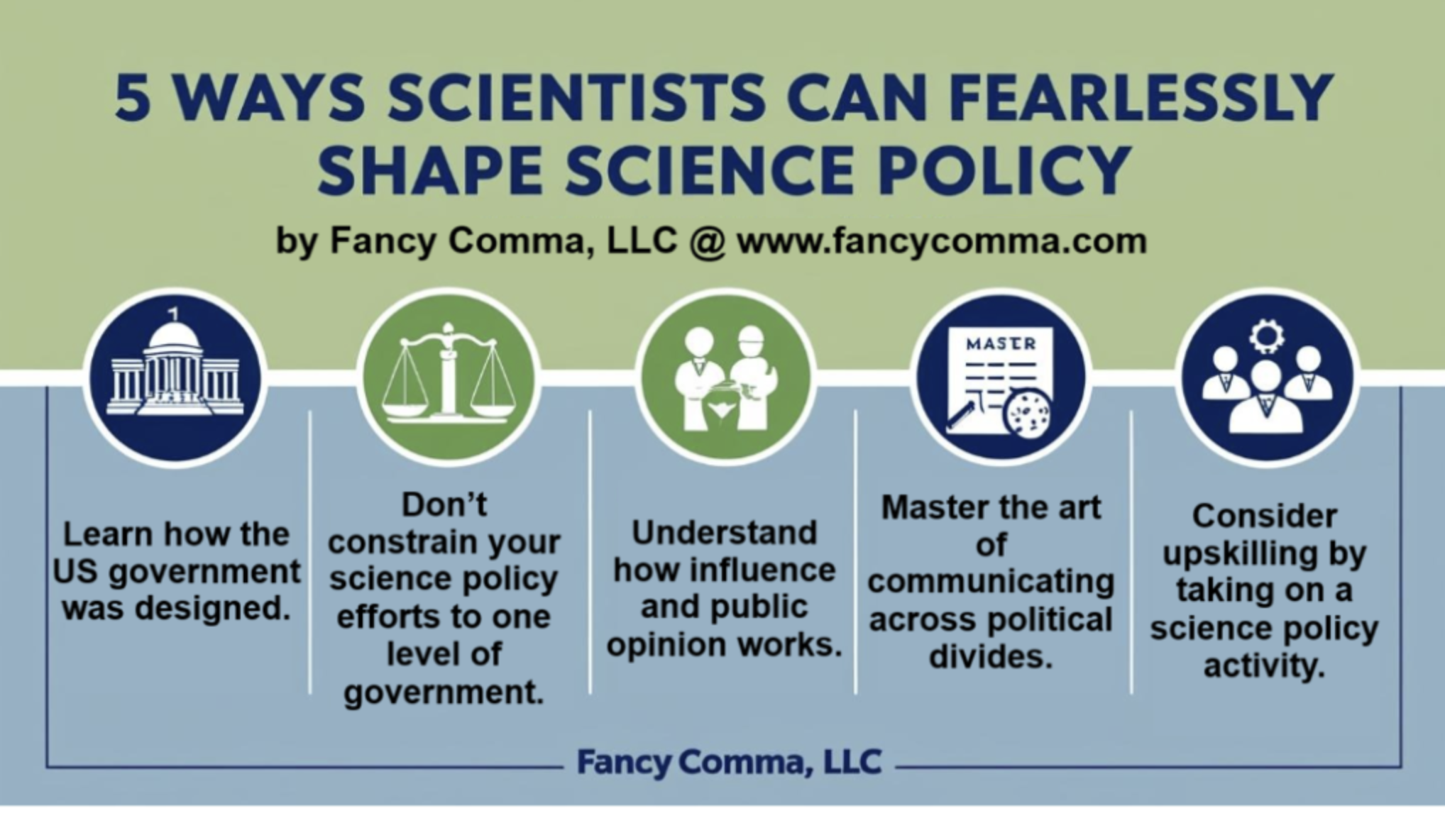

How Fancy Comma Equips Scientists to Engage in Science Policy

At Fancy Comma, the mission is clear: to equip scientists with the tools for advocacy, education, and political communication. As scientists, we need to continue to engage with Congress if we want federal policies that are pro-science. Science does not speak for itself; scientists must. Whether it's engaging in rallies, writing to the newspaper, talking to lawmakers, or having difficult conversations about science with family, every action counts.

Guidelines to help scientists get more involved with lawmakers. Source: Fancy Comma blogs

Researchers are beginning to realize that their grants and funding can be revoked without notice. A key question they should be asking is whether such actions are even constitutional. If something like this were happening to plumbers or carpenters, people would be outraged. Yet, because it’s happening to scientists, a group that is often seen as elite professionals, the reaction has been far more subdued. We tend to take a rational, measured approach, even when the situation calls for collective outrage.

"We want to help scientists get more involved in politics, no matter where they live or their political views," Sheeva emphasizes. "Science is in peril, and scientists need to speak up to counter the anti-science narratives. We need to do a better job of explaining what we do and why it matters."

Cover Image Source: Boston, Massachusetts/USA- April 22nd, 2017 March for Science.