What If We Could Choose What We Hear? Shyam Gollakota on AI-Enhanced Hearing

Mohit Nikalje

Image created using Gemini Nano Banana

Imagine you are walking down to a scenic beach far away from the crowd, listening to those nerve-calming waves gushing on the shore. Suddenly, a rally of noisy children joins in, only to disturb your tranquil moment. Now, you try reaching out for noise-cancelling headphones, but what’s the use? After all, you are at the beach to listen to waves, not to block them out! Here’s a wacky thought: what if you could choose to still listen to the serene waves, without the disturbance from everything around you?

Prof. Shyam Gollakota from the Paul G. Allen School of Computer Science & Engineering at the University of Washington is developing an innovative technology that lets one tune out unwanted noise and listen only to what they want.

Prof. Shyam Gollakota

His innovation-focused lab has so far pioneered battery-free computers, passive Wi-Fi, and origami microfliers. However, a major focus of his work is currently the use of AI and machine learning to augment human hearing. His startup, Hearvana.ai, recently raised $6 million to develop technologies that will enhance the capabilities of AI assistants on our devices, enabling them to listen, understand, and assist us better.

Right now, all this might sound like science fiction, but soon such innovations will be part of our everyday life.

“When we create technology, we don’t want it to just be prototypes in the lab that people can come and experience. We want to see them in the market,” says Shyam, a Thomas J. Cable Endowed Professor and head of the Mobile Intelligence Lab at the University of Washington.

He was a dreamer from his childhood. “I spent most of my time outdoors as a kid. I still remember sleeping on the grass next to a lake and dreaming about things like going into space. But back then, you didn’t have the means to make your dreams a reality,” says Shyam, continuing,

“One of the things that is exciting about my job as a professor is that we don’t need to just dream about things. We can actually build a prototype, making those dreams a reality.”

His interest in auditory communication goes back to his PhD days at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT), where he was working on radio waves. “Sound is a very fundamental thing. Listening to music can change your emotions, making you happy or sad. Animals also use sound to communicate with each other, and in water, these sounds can travel over long distances.”

Compared to many other animals, humans have relatively poor hearing. However, this limitation can be compensated for with technology that helps us hear more clearly. Such technologies are not only valuable for people with hearing impairments but can also benefit anyone trying to listen better in today’s noisy urban environments.

Teaching Machines to Listen Like Us

Have you ever been to a loud party? Whether you enjoyed it or not, you may not have noticed that you were still able to clearly communicate with your friend amid the quagmire of sounds. This feat is possible because our brain can filter out irrelevant sounds and focus on a particular one.

Machines that deal with sound processing, like noise-cancelling headphones, struggle to filter sounds, a challenge often referred to as the cocktail party problem. Noise-cancelling headphones cannot truly differentiate between desirable and undesirable sounds; instead, they suppress background noises based on intensity thresholds, allowing the desired audio, such as music, to be heard more clearly.

To achieve something like semantic hearing, where we can focus on a single sound within a complex mix of sounds, one must use machine learning algorithms like neural networks to separate overlapping sounds and selectively enhance the signal of interest.

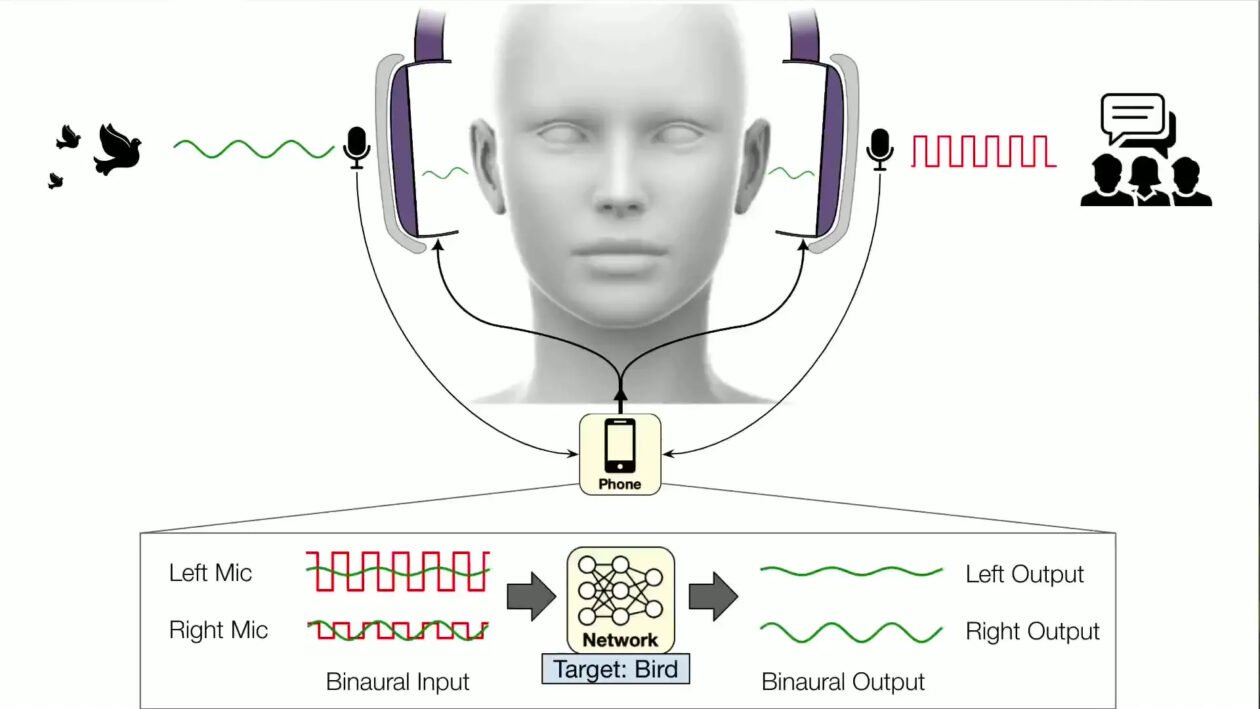

Source: Prof. Gollakota

Neural networks mimic how our brain works and can be trained to identify different sounds and extract only the one that is required. For example, in a study to develop semantic hearing, researchers from his lab trained neural networks on 20 different sounds, which included sirens, speech, birds, alarms, and a lot more. The network can further categorize and isolate a targeted sound from a mixture of surrounding noises.

These neural networks are not as complex as human brains, but are relatively simplistic in comparison. “If you look at animals such as tiny mosquitoes or insects, they have remarkable listening and navigating abilities despite having a very small number of neurons. We can inspire our neural networks by studying them,” says Shyam.

Further, these networks can be deployed to our devices in the form of a mobile application. Sounds from the surroundings can be captured through a microphone in our regular headphones and run through the neural network, which can then identify and provide us with options for what we would like to hear. Such interventions can be helpful to people in professions like the military, construction, and hospitals, where noise can significantly impact a person’s performance.

Semantic Hearing. Source: University of Washington

Neural networks can also be used to create a sound bubble around us. In a 2024 study, his lab constructed a sound bubble by modifying a noise-cancelling headphone with six microphones. These microphones capture sound in 3D space and calculate the approximate distance of a sound source by analysing the intensity of sound and the tiny differences in the time it takes to reach each microphone.

Next, the user is given a choice to select the size of the bubble, which can range between 1 and 3 metres. Sounds that are outside the bubble are significantly suppressed, reducing their intensity by about 49 decibels. To put this into perspective, a whisper is 30 decibels. “Someone who might not have hearing loss, but wants to hear better when they go to a restaurant, creates a bubble and you can hear really well,” points out Shyam, who is noise sensitive himself and possibly that inspired him to develop such technology.

Easier Said Than Built

Translating these ideas into fully functional technologies can be a daunting task. To understand this, let’s compare it with an artificial intelligence platform we all know: ChatGPT.

To get those perfected answers, large language models like ChatGPT consume a lot of energy. However, the technologies Shyam is trying to build can’t afford to expend that much. “To achieve intelligence like augmented hearing, it has to work within the power constraints of a tiny earbud. You can’t have a huge battery, but it still needs to last six to eight hours with very limited compute,” remarks Shyam.

The second problem is the real-time processing. ChatGPT can take a few seconds to provide an output, but hearing has to happen in real time. Therefore, processing must be completed in milliseconds, which requires novel hardware design. These superhuman hearing technologies may also raise ethical concerns, as they could potentially be used for spying or eavesdropping.

“If you’re creating something that billions of people are using, you need to make sure the technology cannot be misused. We can add constraints; for example, I can only listen to someone who is one to three meters away from me. If someone is 30 meters away, the technology, which is meant to be democratized, cannot be used to listen to them,” says Shyam.

Concerns about Artificial Intelligence outweighing the excitement is a general paradigm in all walks of life. Privacy violations, job security, privacy and data misuse are common anxieties people are sharing about AI. However, AI research is clouded by a larger challenge that goes beyond hardware limitations and ethical concerns: the AI bubble, which also worries researchers like Shyam

“Bubbles are more economic in nature; they are about how people are investing money, but I also call it a bubble because there are lots of startups receiving huge amounts of funding because they create a wrapper around an LLM, showing how to query it properly. But is that worthwhile? Maybe a new version of Gemini or ChatGPT could come along and make this wrapper completely unnecessary.”

Like the internet survived the dot-com bubble, AI may also survive a similar burst, if it ever happens. However, one undeniable fact is that AI is one of the most consequential technologies of our era. If used with purpose, responsibility, and ethical oversight, it can support research and innovation and serve the greater good.